Mara Gorman writes the family travel blog Mother of All Trips. Mara’s posts are warm and personal — you feel like you get an intimate glimpse of Mara’s life and experiences in her writing, in addition to all the useful tips and tidbits.

When I saw that Mara had taken a trip to India with her parents as an adult, I asked her to write about her experience in a guest post. For many of us, our parents have had a big impact on our passion for exploring the world. Mara’s story about a trip to India with her father is a moving account of what happened along the way and the meaning of these experiences. Travel provides an extraordinary opportunity to learn more about people — strangers and those that are close us.

Thank you for sharing this Mara!

**

We sat waiting in a narrow hallway. Faces kept peering in the windows and around the edge of the door, jostling and replacing each other at rapid intervals. I wasn’t sure why we were sitting there, because it was obvious that there was no one in the office but the man we had come to see.

“They always make you wait like this,” my father said. “I spent hours, days, sitting in this very spot when I lived here. Sometimes you get in, sometimes you don’t.” I could see my stepmother getting impatient, her leg tapping. But my father seemed serene. At that moment it seemed entirely possible that he might have been sitting in that very chair for the past 30-something years, waiting.

We were in Brahmapuri, India, where before their divorce, before my birth, my father and mother had lived for the majority of their two-year Peace Corps stint in India. I was here to discover first-hand what until now I had only seen in faded black-and-white slides or heard in stories. Stories about the cook my father and mother hired who shared the first name of Thomas with my father and who made incredible things happen in a small metal box that was his only oven. This included not only the curries and flat breads one would expect but a cake shaped and decorated like an Easter egg, which he presented to my lapsed-Catholic mother on Easter morning. Stories about how my father introduced a special heat-resistant breed of chicken to the village which the people took to be so magical and special that they refused to eat their eggs and meat but continued to use up precious resources feeding the animals to keep them alive.

This was the first time my father had been back, and I had tagged along, an adult child wanting a chance to live her former bedtime stories, to see her father as he had been before she came along to change things irrevocably. I also wanted a chance to see what it was like to travel with my father and stepmother, who are real travel professionals, spending a good four months out of every year journeying to all corners of the globe where they hike and camp and trek and eat.

The trip to Brahmapuri which by the year 2000 had grown from a village to what in the United States might be called a large town, came at the end of a week during the course of which we had been on the normal tourist track through Rajastan. We had stayed in a former raj’s palace in Jaipur, rode an elephant, and watched Taj Mahal from the roof of our hotel at sunset. That week had been full of enough decaying magnificence to last a lifetime. But now we were far from the more glamorous itinerary that tourists have followed for millennia. We had taken the overnight train to Nagpur, which is basically the equivalent of traveling from New York or Washington to Detroit. We were solidly in the industrial middle of the country, with no sights to see but Brahmapuri.

I loved India but was also overwhelmed from the minute I landed at 4 a.m., five hours late and without my suitcase, which had inexplicably been left in London by the airline (goodness knows they had enough time to get it onto the plane since we were on the tarmac for four of those five hours). But my father and stepmother immediately stepped in and took charge. They made reservations and plans and led me from hotel to palace to fort and back again. I let them, even as they talked me out of staying in Delhi until my bag arrived, even as they took my passport and some money gave both to a driver at our Jaipur hotel. He promised to return from Delhi with my suitcase and my passport and then miraculously did.

One way I coped with the color, the noise, the smells, the vast humanness of the place was to fall asleep every time I was somewhere quiet. Of course, I was able to do this only because my father and stepmother worked out details and arranged for car rentals and train tickets, while I dozed under lazy ceiling fans. When we got into our chauffeured cars, my father always in the front seat next to the driver I would almost instantly fall asleep, as unconcerned about where we were going as if I had been eleven and not 31.

So I had slept on the drive from Nagpur to Brahmapuri, waking as we pulled into the outskirts of town. We headed first to this small office to find out whether the guest house that my father remembered was still in existence. It was, and when we were finally shown into see the administrator, he told us where it was and arranged for us to stay there. But our primary reason for calling was courtesy and curiosity. My father wanted to see if anyone in Brahmapuri remembered him, if he existed at all in the town’s consciousness.

He wasn’t going to get that confirmation here. My father spoke pigeon Marathi (which to my amazement he had managed to pull out of his brain after all those years away) and the small man with big glasses and shiny brown shoes spoke pigeon English. They communicated, but not much of importance was said. They knew no one in common; this man knew nothing of the work my father had done. Before we got back into the car, he and my father posed for a picture in front of the office, shaking hands as if they were going to appear on the front page of the newspaper.

Our next destination was the home of the town’s wealthiest Brahmin family who had taken my father and mother under their wing, rented them their house, and basically permitted them to carry on their Peace Corps work with a weary air of noblesse oblige. After a short drive we arrived at a large and pretty blue and white house, its front courtyard dappled with shade. A surprisingly large number of people began emerging from the house, among them a man and a woman who looked to be about my parents’ age. A bright yellow sari covered her ample frame; he was wearing long sleeves and a smile. There was much nodding and bobbing and many namastes and finally some looks of recognition. Success! This family knew my father, they remembered him. And we were ushered inside and showered with plates of food – samosas and fritters and galub jamin, a kind of honey-dipped donut hole that is inexplicably delicious. We sipped water from our filter bottles and ate and ate and nodded some more.

“You were at my wedding!” she of the yellow sari told my father, shaking his finger at him. He laughed, gesturing at the plates of food in front of us.

“I ate so many galub jamin that I thought I would burst!”

Was she batting her eyelashes at him? “Yes, but you were so skinny!”

We sat there eating for hours and then left for a nap at the guest house before returning that evening to eat still more. At dinner, four little girls, daughters of the current patriarch (who had replaced his father, the old man my father had known) watched us from the kitchen and then posed shyly for a picture in the courtyard.

After dinner we tried to wander the streets. My father kept dropping details, small nuggets of information that I gobbled greedily. He talked about how everyone in town thought he was old when they lived there (although he was only 22) because his hair was so fair. He talked about the scandal that ensued when he grew a beard and people thought my mother had taken a new husband. He pointed out the house where he and my mother had lived – its current resident peered at us through the curtain that served a front door.

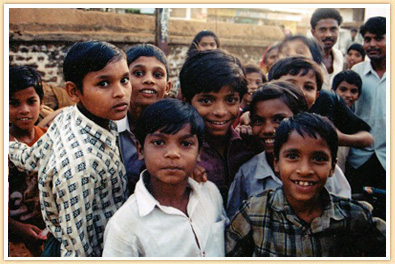

While we walked, there were people everywhere – a swarm of children and some adults followed our every move. People stood on rooftops to see us, and peered out of alleyways. People asked us to sign notebooks, newspapers, any scrap of paper they could find. We moved through the village slowly. According to my father, it was like this almost every time he and my mother left the house. I have no idea how they managed to live any semblance of normal life – it must have been a small taste of what it’s like to be Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie.

My father was very happy to see lots of eggs for sale in the street stalls. Clearly the citizens of Brahmapuri had recovered from their chicken worship in the years since he had been there last.

While we walked slowly, snapping pictures all the while, one especially bold young man in a baseball cap asked my father if I was married. He was shocked to find out that I was and that I was there with my father and not my husband. He wanted to know why I was there.

My father smiled slowly, “Well,” he said, “she wanted to see Brahmapuri. That’s why she came.” And he was right and wrong. I had come not only to see the place as it existed, but as it had once been, before I was even born. I had come to see what person my father was in this utterly foreign place, and what person he had been before my existence. I had come to travel with my father.

travel recommendations, inspiring adventures, and exclusive travel offers

travel recommendations, inspiring adventures, and exclusive travel offers

Beautiful post, Mara. I took a similar trip with my father. Very moving and enlightening to return to a spot filled with so many memories and new experiences. Loved all of the details and especially loved the final paragraph.

What a beautiful story! Thank you for sharing. That must have been a great trip and wonderful experience for you to be able to trace back and share it with your dad.